Shutesbury resident who sued school district over lead in water in 2017 and 2019 urges district to finally act in 2026

This is not the first time the Amherst schools have undergone voluntary lead testing, or results have raised public concern. In the fall of 2016, then brand-new superintendent Michael Morris signed up the schools for the same lead testing that was just performed under Superintendent Xiomara Herman.

Amherst schools were not alone in doing this testing. According to an article in The Daily Hampshire Gazette, the state’s program took water samples from 818 schools in 153 communities between April 2016 and February 2017. In Hampshire County, 21 out of 25 participating schools (or 84%) were found to have high levels of lead in at least one fixture, with samples testing water that had been in the pipes for eight to 18 hours.

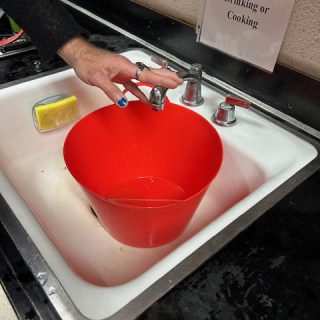

Nine years ago, The Graphic published a story, Lead tests reveal contaminated water at all ARPS schools, which indicated that three water fountains and one sink at ARHS had high levels of lead. At the middle school, 23 water fountains and faucets had high levels of lead before “flushing” the water, after which seven water fountains and three faucets still showed high amounts of lead. All elementary schools tested showed faucets and water fountains positive for lead, as well.

Morris’s solution at the time was to embark on the replacement of some faucets and to require flushing protocols to minimize lead levels in the water. In an opinion piece for The Graphic in 2017, a student questioned whether these fixes would work, but affirmed that the administration had “taken the kind of action that reassures staff, students, and families that the schools are taking charge and fixing the issues” (Solutions for lead-laden water).

According to an article in The Daily Hampshire Gazette in February of 2019, Morris told reporter Scott Merzbach, “that the district’s actions of removing and replacing fixtures in the schools already meant that the drinking water in both the regional school buildings and the elementary schools in both Amherst and Pelham is safe for students and staff.”

Morris congratulated those he said had helped make it happen. “Thanks to the work of our facilities department, in collaboration with the Amherst Department of Public Works, all of the drinking sources in all of our buildings now exceed the standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection for both lead and copper,” Morris said.

However, Shutesbury resident and retired hydrogeologist Michael Hootstein wasn’t so sure that was possible and had filed (in 2017)—then amended and refiled (in 2019)—a lawsuit in US District Court, at which point he told The Daily Hampshire Gazette, “I am alleging the drinking water is as lead-contaminated today as it was on day one.”

After his initial suit, Hootstein told The Gazette he wished for the school to “provide bottled water to students and install new filtration systems to ensure that people do not consume lead-tainted water in the schools.”

Because Hootstein was attempting to represent his grandson in the initial lawsuit, the judge had ruled against him, but in his successfully amended complaint, he noted that “the drinking water is causing harm to people in schools” and that his rights had been violated.

According to the Daily Hampshire Gazette, Hootstein’s lawsuit, with oral arguments heard in January of 2019, “claimed that not eliminating the lead from the water was a violation of children’s and parents’ bodily integrity rights under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, and a violation of Article 97 of the amendments to the state’s Constitution, which states ‘people shall have the right to clean air and water… and the protection of the people in their right to the conservation, development and utilization of agricultural, mineral, forest, water, air and other natural resources is hereby declared to be a public purpose’.”

The Graphic spoke to Hootstein again this year to ask him what he thought of the fact that the test results in 2025 were strikingly similar to the results from 2016.

He said he is frustrated that lead poisoning at our schools has persisted years after initial statewide lead testing. “The state had provided about $3 million for voluntary lead testing of drinking water [years ago]. This was pretty well reported in the news,” he noted, and when the results came back, “they were shocking, and I was appalled.”

He remembers that one of the highest values was found in the boys’ and girls’ locker rooms. “I reached out to the school committee and the former superintendent, but no one wanted to look at the data,” he said.

In fact, he said, no matter where he turned, he found that people wanted “nothing to do with the solution.”

Additionally, the state either couldn’t or wouldn’t fully fund solutions, and “towns were left to solve problems themselves,” said Hootstein.

The Graphic reached out to Morris in January of 2026, in an effort to understand the claims he made in 2019 about the water being safe, the fixtures being mitigated, and the flushing protocols working, especially given that recent results show tainted water across Amherst schools.

Morris only said that he trusted those who told him the water was safe. “During my time as superintendent, I relied on Facilities and Public Works specialists to assess testing data and make technical determinations, as those kinds of technical judgments were handled by the experts advising the district,” he told The Graphic.

Hootstein was clear: “Lead in drinking water is a dangerous neurotoxin,” he said, adding, “Children are the wealth of our nation” and “should never be knowingly exposed to poison in schools.”

Hootstein finds it concerning that while the Department of Public Health has documented lead’s effects on the body and classifies it as a dangerous neurotoxin, our society has not effectively stopped children’s exposure to lead.

“When the government deprives us of our constitutional rights, people may seek a solution in court. Lead exposure cases can be constitutional violations,” he said.

To him, the solutions are clear. He urged the Superintendent to immediately begin marking “every single water source as not safe for drinking if it contains lead.”

Hootstein also still believes schools should install filters at every drinking outlet so students can fill their water bottles. He said lead is relatively easy to filter from drinking water if systems are maintained, and filters should be checked regularly to know when replacements are needed. “This system should be used in schools, state offices, and large corporations,” he said. The price for each unit would be around $2000.

The high school has a few water bottle filling stations, but many have not been maintained.

Until these steps happen, he advocates for everyone to “take the poison away from your children,” and “to bring their own water until full fixes are made.”

For him, addressing lead as a toxin in drinking water is an all-hands-on-deck situation involving “school committees, school staff, town officials, parents, and the state.” Hootstein said communities should not rest until they are met with “responsibility and action.”

“We must work together to ensure safe drinking outlets for students,” he said. “We need to follow the data and solve the problem.”