The ‘cure for hate’: students attend anti-extremism workshop sponsored by Karuna Center for Peacebuilding

On Thursday, October 5, 24 ARHS students spent their D period and Flex Block in the library for a Psychology of Violence and Hate Leadership Training sponsored by The Karuna Center for Peacebuilding and linked to the Brave Schools Initiative.

Assistant Principal and social studies teacher Samantha Camera brought the training to ARHS. It was led by Tony McAleer and Robert Orell, both former white supremacists who exited movements of hate and currently spend their adult lives working to foster peace and justice.

Staff members librarian Ella Stocker, Restorative Justice Coordinator Aaron Buford, Dean of Students Diego Sharon, and Camera also attended the workshop.

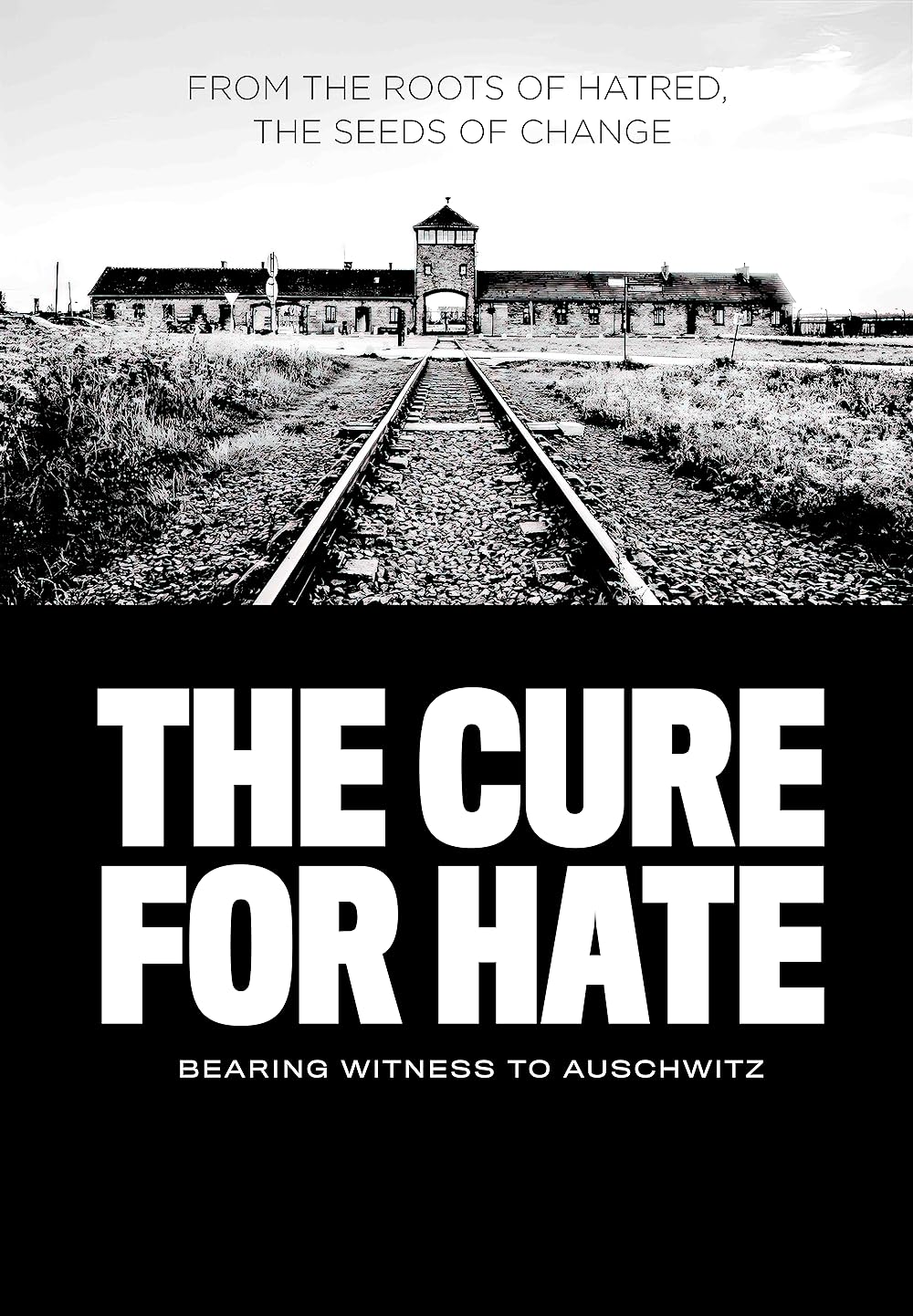

According to his bio, McAleer is the author of a book and film called “The Cure for Hate.” He also co-founded the non-profit Life After Hate, an organization “that helps people leave white supremacist movements behind.”

Before coming to this work, he acted as a leader of one of the largest Neo-Nazi skinhead organizations, the Aryan Resistance Movement, and an organizer for the White Aryan Resistance and Aryan Nations.

After going through thousands of hours of counseling to understand how to break from hateful thinking and “reconnect with humanity and with society at large,” he is committed to helping others do the same.

Orell is also “an expert in violence prevention.” He is a Swedish citizen and according to his bio, was involved in the Swedish white power movement in his early teens. He then worked with an organization called “Exit Sweden” that helped him leave Neo-Nazism behind.

Orell later became the director of the organization that assisted in his departure from hate groups and now works as a national expert on “setting up exit programs.” He also co-teaches a course on the Psychology of Violence and Hate.

The workshop began as students introduced themselves and discussed their familiarity with and understanding of violent extremism. Next McAleer and Orell talked about their lives, showing video clips from the documentary, and engaging students in a few short dialogue exercises, followed by a Q and A with the students and the leaders.

Most students expressed minimal to no knowledge of the difference between extremism and violent extremism, so the discussion began with a question: “Do the ideas promote violence or not?” Extremism is considered violent when violence is used as a means to change society or spread beliefs.

I’d like students to choose compassion over fighting. That’s the message of this Brave Schools Initiative.

SAM CAMERA

McAleer and Orell addressed the students’ most pressing questions about their entrance into these hate groups and how their minds underwent a profound transformation after leaving. McAleer expressed feeling isolated and weak and said he sought a sense of belonging which played a pivotal role in his joining one of these groups.

His first interaction with the skinhead Neo-Nazi faction was at a drive-in movie when two men from the organization tried to rob him of his shoes. He recalls feeling powerless. He now realizes he ended up being a victim to the idea of “befriend the bully, become the bully.”

The same men who tried to rob him and became his best friends ended up also leaving the group; one was expelled for being a quarter Jewish.

Inside the movement, he initially felt a sense of brotherhood, belonging, and power that he had been searching for and he spent 15 years loyal to the movement. “At the age of 20 I declared that I would be dead or in jail by 30 as a symbol of [my commitment to upholding] white supremacy,” he said.

McAleer left the group to devote more time to parenting his young children, as he was a single father. “I left the movement, but the movement didn’t leave me,” he said. It took him many years before his mentality changed. “It’s not just what people believe, it’s who they are,” he said. “It becomes their identity.”

After leaving the movement McAleer felt great shame, guilt, and embarrassment that he had joined it and integrated its beliefs into his life. After six years he found himself face to face with his first therapist. From there, he said, “My healing journey began.” Through extensive counseling, he was able to reflect on his “actions and ideals and undergo a deep transformation.”

McAleer and Orell have devoted their adult lives to “understanding and transforming their own identities away from white supremacy and towards compassion.” Throughout their training, they emphasized the importance of three core principles: “courage, compassion, and curiosity.”

“My hope is for students to be able to recognize concerning behaviors and learn to include students that have been isolated or excluded,” Camera said, rather than becoming vulnerable to hateful or extremist thinking, one of the training’s objectives.

While Camera believes that there isn’t a problem with violent extremism at ARHS she does acknowledge the existence of violence. “I’d like students to choose compassion over fighting, and that’s the message of this Brave Schools Initiative,” she said.

Students who attended the training will have the opportunity to engage in other activities throughout the year and to take on a leadership role in spreading the message of compassion and inclusivity.