Lead testing reveals tainted water across Amherst schools

Superintendent Xiomara Herman sent a letter to families and staff in November 2025 sharing the results of voluntary lead testing that took place at ARHS, ARMS, Pelham Elementary, and Crocker Farm in September. These tests revealed dangerously high levels of lead in 20 locations across the middle and high schools, including faucets in the kitchen at ARMS and in the health office at ARHS.

The testing took place as part of the MassDEP Water-Smart Lead Testing Pilot Program, in advance of mandatory statewide regulations that will take effect in November 2027.

Two samples were collected at each water fixture: a “first draw” after an eight to 18-hour stagnation period, and a “flush” sample taken after running the tap for 30 seconds. While nearly all lead levels were significantly lower after 30 seconds of flushing, eight of the 20 fixtures where lead was initially detected still yielded results above the laboratory detection threshold of 1.5 ppb (parts per billion).

The lead is coming not from the reservoirs and town wells that supply Amherst’s water, but rather from old pipes in the ARMS and ARHS buildings. The middle school was built in 1969, while parts of the high school were built in 1955.

According to a 2023 UMass Amherst study investigating the risk factors leading to lead in MA schools, “50% of water samples from buildings constructed in 1986 and earlier had a water lead level of 2.1 ppb or higher,” as they predate the 1986 federal Safe Drinking Water Act Amendment, which required the use of lead-free piping.

Lead is widely recognized as a serious systemic neurotoxin, particularly known to cause nervous system damage in the developing brain during childhood. However, while lead exposure is most dangerous to young children, it is also very harmful to teenagers and adults.

Regardless of one’s age, drinking lead-contaminated water can cause serious lifelong health problems, including cardiovascular issues and decreased kidney function. The Environmental Protection Agency states that there is “no safe level of exposure to lead.”

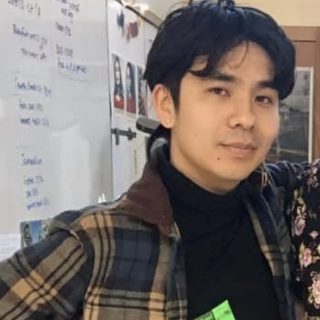

A teacher who routinely drank contaminated water

Of the 20 fixtures testing above the 1.5 ppb threshold between ARMS and ARHS, three tested higher than 15 ppb of lead, the EPA “action level” for lead in drinking water. One such faucet, located in an unassuming kitchenette attached to French teacher Frank Vaissiere’s classroom in room 143, tested at a whopping 258 ppb of lead upon first draw.

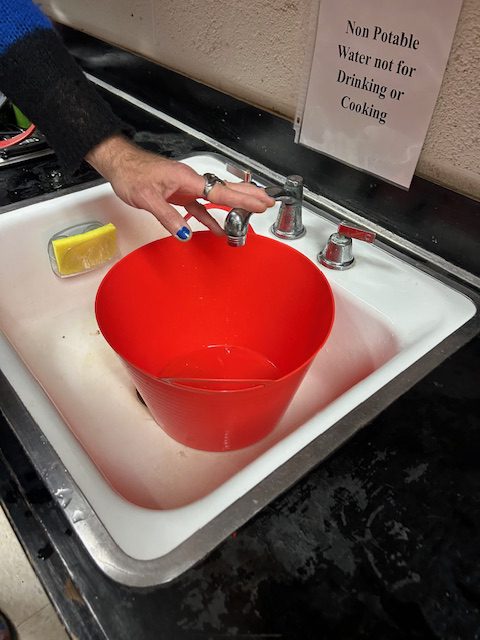

While lead concentration decreased to 10.1 ppb after 30 seconds of flushing—a level still dangerous for consumption, but less drastically so—Vaissiere had been drinking drip water that he collected from the leaky faucet overnight.

That water was sitting more or less stagnant in the pipes, and it likely contained lead concentrated at first draw levels. “Flushing would have been probably a better thing to do,” he said. “But in my, you know, ‘Let’s conserve water’… overnight I could fill up a huge bucket.”

Vaissiere has only been in room 143 since the beginning of the 2025-26 school year, when he took over the room from now-retired Spanish teacher Mari Vicente. However, for the first two and a half months of the year, before the tap was turned off, Vaissiere was boiling drip water to make tea and coffee nearly every day.

Boiling lead-contaminated water actually increases the concentration, because lead doesn’t evaporate, but the water does.

When the tap in 143 was first shut off, Vaissiere had no idea how high the lead levels were in his sink compared to other water fixtures in the school, and paid little attention to it. At first, it just seemed like yet another maintenance issue to add to the list.

Vaissiere described his initial reaction. “What else is next? I’m struggling with technical issues every day where the projector will not connect, or then we have [no] heat, and then this guy comes in, shutting off the water,” he said.

Now, though, Vaissiere is growing concerned about his health. A colleague recommended that he get a blood test. “Maybe I’ll do that [testing] and see what it says, because I think the [lead] level is quite alarming,” he said.

Vaissiere is concerned for the health of his colleagues as well, as the sink in the language department office (room 148) tested at 12.2 ppb of lead upon first draw.

“Even though the levels are lower in 148, everyone was boiling water, making tea, coffee, or possibly drinking the water straight from the tap,” he said. “We were relying on this source of water for a lot of things.”

Vassiere expressed frustration that the ARPS administration did not order water testing earlier or more regularly, which might have kept him and others safe from lead exposure in the first place. “I would like [the administration] to be on top of everything,” he said. “This [testing] is something that should be done once a year, at least.”

Middle School results equally alarming

Meanwhile, lead testing at ARMS identified 11 fixtures with lead levels above 1.5 ppb, and 3 fixtures exceeding 15 ppb. Several of these fixtures are used for drinking water and food preparation, raising concerns about daily exposure to students and staff.

One of the most concerning findings was the kitchen kettle, located across from the lunch line, which tested at 21.2 ppb, more than 40% above the EPA action level. Since heating water increases its lead concentration, contamination accumulates with every serving as the kettle is heated repeatedly throughout the school day.

In school kitchens, kettles are commonly used for preparing instant foods, sauces, or meals where adding hot water is required. With this use, lead ends up directly mixed in and eaten by students and staff.

Nearby, the food prep sink near the kettle had lead levels of 14.8 ppb, though flushing reduced it to 1.3 ppb. While cleaning utensils and meal prep surfaces with contaminated water provides a lower risk of digesting lead, residue can remain, especially on porous surfaces.

Though the flushing protocol tends to reduce lead levels in a handful of contaminated faucets, other results indicate that flushing is not always a reliable solution. In some cases, there was little difference, or even worse lead results. For example, the 1st hall cooler outside the auditorium had 12.0 ppb, and after flushing reduced to 11.7 ppb. Room C-14 started with 13.6 ppb and reduced to 11.5 ppb. The health room went from 4.5 ppb to 1.8 after flushing.

The most concerning location was Room C-28 (Drama room), where levels increased dramatically after flushing. What began with 87.0 ppb increased to a staggering 209.0 ppb. This suggests that running water can pick up more lead along the way, contradicting the idea that running the tap mitigates contamination.

Future Plans

New regulations will come into effect beginning in November 2027, which state that “all community water systems will have to offer lead testing to at least 20% of the elementary schools and 20% of the childcare facilities in their service area each year until all such facilities are given the opportunity to test,” according to MassDEP.

While these regulations will not mandate regular testing at the secondary school level, Superintendent Herman opted to take advantage of the opportunity to run tests at the middle and high schools this fall. “It was important to me and to our new Operations Director as we work to fully understand the current condition of our facilities,” she wrote.

Herman is still unsure whether she will request testing in the ARPS secondary schools again, or when that might take place. “For safety reasons, I may want to retest,” she said. “I’m not sure if it’s going to be in 2027.”

However, she is committed to staying informed and engaged as the lead issue evolves. “I come from a place of, if I know better, I can do better,” she said.

While noting that she is not an expert in this area, Herman said she did not know whether it would be possible to achieve zero lead in the ARPS water supply, given the age of the district’s buildings. “My goal would be for us to have limited to no [lead], but that would be unrealistic,” she said. “The aim is to mitigate issues and make sure we address them timely.”

*Graphic Editor Elizaveta Ivanova contributed reporting to this story.

Note: This is the second time within a decade that the school has received alarming lead testing results. The Graphic reached out this month to a Shutesbury resident who sued the school district in 2017 and 2019 over tainted water to learn more.