Kara Bear takes lead in organizing Harvest Dinner to address food scarcity, highlight Indigenous wisdom

Light chatter and the smells of good food wafted through the halls of the Lighthouse School, 92 Race Street in Holyoke, on the evening of Wednesday, November 27. With a pristine commercial kitchen for food preparation, and ample space for community gatherings, it was deemed it the perfect place to host the Holyoke Food and Equity Collective’s (HFEC) Harvest Dinner.

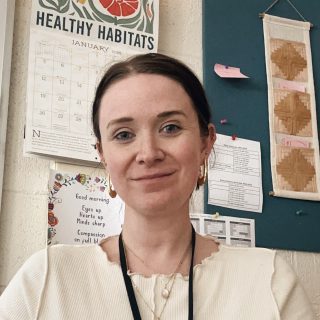

ARHS band teacher Kara Kahgee Bear is one of four co-directors of The Collective, which mostly addresses the lack of quality food access in the most populated areas and lowest income areas of Holyoke, in addition to access to other essential resources. The aim of the dinner was to address this issue through direct support, feeding the community, but it included a secondary theme of spreading Indigenous awareness.

“I think it’s maybe impossible to exist as a Native person in this country without thinking and talking about food sovereignty; it’s a key part of sovereignty in general,” Bear said. “As a collective, we have a passion for food sovereignty and food justice, but we also recognize that this work does not have to feel heavy/serious/depressing all of the time. We can fight food inequity, spread awareness and information, and increase food access while also having fun, and throwing a party.”

The Harvest Dinner was the brainchild of Bear’s friend and fellow co-director, Oaxacan chef and Holyoke resident Neftali Duran, age 46. He devotes part of his career to creating opportunities for people to come together in community, to share delicious, quality food, and he was the head of the menu and lead cook for the dinner. The event required a lot of additional preparations, including booking the location, sourcing the ingredients, planning the activities, getting the word out, and selling tickets, which was taken on primarily by HFEC member Margot Wise. Most of the labor was volunteer work was organized by done by The Collective and community members, such as teens from the Lighthouse School managing tech during the event and helping in the kitchen. Advertising was done primarily online through Facebook and Instagram, along with a mention on the 413 on NEPM while two members of The Collective were featured.

A dinner of champions was served on the night of the 27th. Squash, bean, and root vegetables were major elements, incorporated into dishes such as roasted squash and butternut squash soup, carrot soup, black bean paste, tepary beans, and roasted regular and sweet potatoes. Various meat entrees included ground bison with kale, bison steak, duck confit legs, and roasted turkey. “Literally the best turkey I’ve ever had in my life,” said Bear.

These were complemented with salad, coleslaw, and refreshments like lemongrass thyme tea sweetened with maple and pineapple and hibiscus agua fresca. Desserts followed the main meal, made by students of The Lighthouse School: pumpkin pie bars and cookies made with acorn flour that was processed by the students led by Wise.

Ingredients for The Harvest Dinner were sourced sustainably. The vegetables served were donated by Atlas, Brookfield and Mountain View Farms and the bison was from Adams farm in Athol. The black beans were brought by Chef Duran all the way from his home in Oaxaca, Mexico. Maple products, honey, and wild rice were purchased from Tocabe Indigenous Market based in Denver, Colorado.

Before everyone sat down to eat, there was a guest speaker on the mic for 30 minutes, an invited Native elder and friend of Bear’s named Joyce White Deer Vincent. She entertained the audience with her excellent storytelling and had everyone laughing with her as she had members of the audience act out the characters while teaching the importance of sustainable hunting practices. Marita Banda, an ARHS English and Special Education teacher who attended The Harvest Dinner with English teacher Sara Barber-Just said, “It was really nice to hear her storytelling. I thought it was nice how they got the audience involved.”

A trivia competition was also held in groups of four, with three themed rounds of Holyoke trivia, Indigenous trivia , and food trivia. Banda and Barber-Just formed a team with a new person they met at their table. “It was nice to get to know someone else there, and the community-family style seating really helped bring people together,” said Banda.

There was also a plethora of small activities, such as giant jenga, coloring, and games of “eat the donut off the string.” While the atmosphere was cheery and bright, a current of inequity awareness flowed strong throughout the evening. “People need to understand inequities to fight against them. But this doesn’t mean you need to (always) kick up peoples fears or feelings of powerlessness by overwhelming them with stats and details,” said Bear. “Sometimes, you can be just as–or more–effective with humorous stories that also teach but are easier to remember, or with trivia that gets people thinking about important topics in a more engaging way.”

Open to all, children and adults alike enjoyed the festivities of the dinner. One example of how the Harvest Dinner infused social justice and food access elements with subtlety is offering a sliding scale entrance fee to help cover the cost of ingredients, materials and labor.

The Collective insisted that local Indigenous people and elders ate for free. Whether someone came to the dinner because they could afford a hot meal for their family, or they were looking for a fun, community-centered evening, they were welcomed with open arms, and the turnout was epic.

Around 100 smiling faces congregated to share food and laughter during the dinner. “Enough people paid extra to offset these comped meals, and we were still able to cover our expenses and raise some funds for the next project,” said Bear, “Turns out, most times that you give people the choice, some have higher need and some offer higher contributions, and it all works out… it’s almost like we don’t live in a world of scarcity after all.”

All in all, the evening was a success. Aside from fundraising $1300 to go towards their community work, The Collective’s efforts to bring the community together resulted in an inviting, entertaining, and nourishing gathering that rewarded both the organizers and attendees. Most importantly, The Harvest Dinner served as a space for people to learn about matters of food insecurity and raising Indigenous awareness without unnecessary tension.

As Bear put it, “People came, ate great food, and had a great time. One person came up to me after and said “Wait, I thought we were going to have a Native speaker.” The fact that she didn’t recognize the storytelling–I mean, there was literally a Native elder on the mic for 30 minutes–as a speech on food sovereignty served as proof of concept for me.”

While this marked the first ever Holyoke Collective Harvest Dinner, the members of HFEC participate in a wide variety of community engagement such as helping host an annual Intertribal Powwow in Amherst, the Odenong Powwow. This is a Native event featuring drumming and dancing exhibitions and competitions, community dancing, and Native craft, clothing and food vendors. There are many many Powwows throughout the US and Canada and they can be specific to a particular tribe or, as in this case, “Intertribal”

Held the Saturday and Sunday of Memorial Day Weekend, this will be the fourth year in a row that the Powwow takes place at Amherst Regional High school and is currently the only Powwow in Western Massachusetts. Events like this are important opportunities for Native people to come together, and for non-Native people to learn about and beauty, joy and community of Native culture.

“It is particularly important to Justin Beatty, the founder of the Odenong Powwow, to host a Powwow in Amherst given the genocidal history of the town and its namesake [Jeffery Amherst],” said Bear, “Justin, myself, and our friend Feyla organize and facilitate the event with additional volunteers. We’d love to include as many ARHS students as are interested this year! And if by some chance you are reading this and you are an ARHS student with Native American heritage, please feel free to reach out to me! I know it can be an isolating experience.”

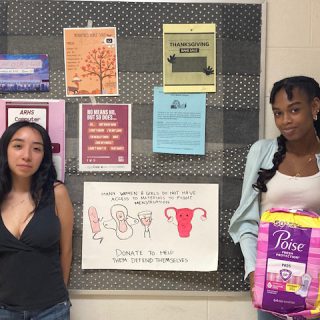

A big project of The Collective’s is a diaper drive and distribution program, started by Bear, that communities with children in Holyoke have come to rely on. The program ensures that 20 diapers are delivered twice a month per child to families in need. The Diaper Bank is funded monthly through $5-$25 donations given mostly by locals.

The collective receives money in multiple ways, one of which is direct donations through the fundraising platform Givebutter. Other methods include applying for grants and independent donors or supporting organizations. Since the diaper drive has recently experienced an increase in demand, the HFEC is campaigning to raise its funding. They are currently striving to amplify monthly donations to $1000 by the end of December.

With food sovereignty being one of HFEC’s biggest concerns, they make sure to do their part in helping community members source their own nourishing food in sustainable ways. They lead and annual bucket garden project, in which they donate buckets with fertile soil and pre-planted seedlings so that people can growing vegetables in their homes without the necessity of an in-ground garden.

The Collective also invests in providing entire garden beds, a more involved project where volunteers come to each home to install the garden beds and fill them with soil. “We have also recently installed a community compost center at one of the local community gardens, which has a lot of folks excited about duplicating that project in other parts of the city, “ said Bear. The HFEC partnered with the Chamber of Commerce in order to help start the Holyoke Farmers Market, partnering with a local farm to run a mobile market during the summer as well. They have been trying to change Holyoke policy to permit residents of Holyoke to raise hens, but so far have not been able to get the town to change the system.

The Collective continues to work and fight for all of this and more, all while three of the four codirectors have separate full-time jobs. “We all work together to take care of logistics for our various projects as needed and as we are able,” said Bear. One thing the activism group is still in uncertain of is their plan to expand in numbers. While the ideal member would be a resident of Holyoke who brings a passion for collaboration and infusing food justice and other access-based projects into their community, as the HFEC dances the fine line between a business and a nonprofit, affiliation and personal income systems are complicated.

Bear said, “We both want our work to be volunteer-based and stay outside the for-profit or non-profit industries, and believe people should be paid for their labor. It’s something we’re still working out.”