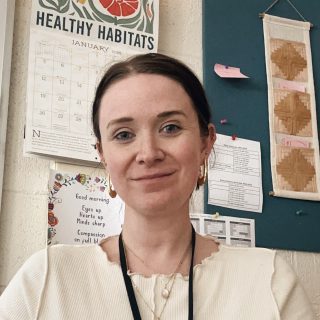

Dr. Woodruff in the house: getting a doctorate while working full time

Nathaniel Woodruff wears a lot of hats: not only is he a science teacher at ARHS, but he is the Engineering Department Head and the Nordic skiing coach, on top of being a busy dad. However, this year, he added another title–doctor–after finishing a six-year-long project to earn his Ph.D. at UMass. I spoke with Woodruff to learn about how he managed to complete this educational goal while also teaching dozens of his own students.

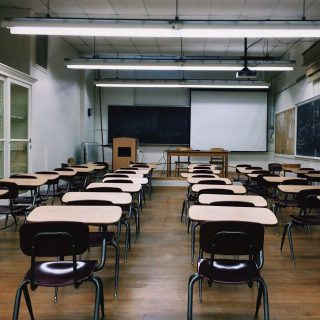

At ARHS, Woodruff teaches all the Physics classes, Engineering, and in other years Environmental Science and Chemistry. He has been teaching at ARHS since 2008, but in total, he has been a teacher for 25 years. He began working on his doctoral degree ten years into his job at ARHS, in 2018.

His doctoral dissertation is about “using technology in healthy ways to motivate students.” One way he researched this question at ARHS was by working with ninth graders by “having them use a curated collection of resources in lieu of a textbook.” Woodruff chose this topic because of his experience during his Fulbright sabbatical to Finland in 2017.

He said he learned a lot in Finland by studying phenomena-based education. “Phenomena-based education is teaching around topics instead of disciplines,” he said, offering the example of offering a class about climate change rather than a traditional science class but still teaching the same skills. “We [can] use climate change to learn about chemistry, biology, and physics,” he said.

Woodruff toured the whole country on his sabbatical and got to see “really cool uses of technology in education but also differences in how students were motivated.” One thing he noticed that piqued his interest was that “students there were much more self-directed.” They “learn a lot more on their own with the teacher being seen as a resource” rather than a guide.

Woodruff’s doctoral advisor was Tori Trust, a Professor of Learning Technology in the College of Education at UMass. Trust helped Woodruff by keeping him on pace. “[A thesis adviser] is like a guidance counselor,” he said. She also helped as an editor for Woodruff’s dissertation.

In it, he laid out four main questions: how students rate online versus textbook resources; how interesting, relevant, and up-to-date each resource is; if students are in an environment to be motivated, their locus of motivation and the outcome on the unit test.

Woodruff found that for students a textbook was very comfortable but they didn’t learn much from it because the goal was so straightforward that students could just run on autopilot and find all the answers.

With curation, “students had to find their own resource which led to much more learning on a deeper level. Woodruff said oftentimes students would prefer the textbook even though it led to worse outcomes because they believed it aligned more with what would be on the test.

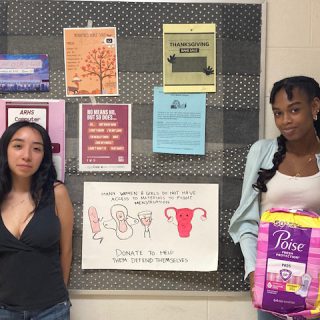

To measure motivation in students, Woodruff used a theory of motivation which states that to be able for students to be motivated, their basic social emotional needs must be met. One of these requirements is for students to experience belonging, to feel that they are “part of the learning community.”

Autonomy is important, as well. Students need to feel they have “some sort of a choice so that you’re not just being driven but are given some sort of control.”

In terms of his own motivation, Woodruff said it required a lot of discipline. To work on his Ph.D. while teaching was sometimes a grind. “I would get up between around four in the morning [to work on it each day,” said Woodruff.

Though he is proud of the result, he joked that it “definitely took years off my life.”

“I don’t think the systems are designed to be working full-time as a teacher and get your dissertation,” he said.