Road to reconciliation: a Rwandan genocide survivor speaks out

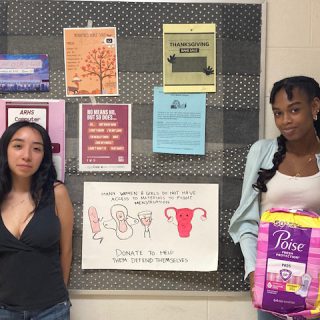

On September 17, students in AP History and Holocaust classes at ARHS attended a powerful event in the library where they heard from Rosette Sebasoni, a survivor of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. This event was sponsored by the Karuna Center for Peacebuilding’s Brave Schools Initiative and was coordinated by Assistant Principal Sam Camera.

In this moving and powerful presentation, Sebasoni spoke about her own personal experience and her part in a post-genocide process of national reconciliation, healing, and forgiveness.

Social studies teacher Christopher Gould brought his classes to the event. “In terms of connecting to issues of colonialism [and] peacemaking, [the Rwandan genocide, of 30 years ago] is still pretty current,” said Gould. Hearing about it was an important opportunity for his students, noting it “is a way to see how communities in a different place have tried to work in order to make something better.”

Sebasoni, a survivor of genocide, has spent the past year gathering stories about not only the genocide but also reconciliation. According to Wikipedia, “The Rwandan genocide, also known as the genocide against the Tutsi, occurred between April 7 and July 19, 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu militias.”

One story that stood out to Gould was a description Sebasoni gave of a Tutsi girl falling in love with a Hutu boy whose father had killed much of her family. Of course, her family would never allow this relationship to continue.

Through reconciliation practices that were put in place after the war, the boy apologized to the girl’s mother, who also felt sorrow for having forced the couple to break up. In a way, sort of slowly over time, “they miraculously reconciled,” Gould recalled.

During the period after the genocide, the government of Rwanda as well as the United Nations set up programs to foster justice and reconciliation, that were highly in-depth and successful, like the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, and the The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

“Something like two-thirds of the perpetrators and survivors trying to reconcile have worked,” said Gould. Part of the process involved survivors telling their stories, whereas the other part involved perpetrators confessing to horrific crimes. Survivors were able to eventually understand that many of the perpetrator’s actions were a result of having been brainwashed and manipulated to do what they did.

The students were impacted by these stories, as well. When Gould asked them if they would have been able to practice forgiveness in the way these people have, many said no. “Genocide is about as dire as it gets,” said Gould, who noted that reconciliation practices that “create accountability and healing after [such violence]” are incredibly powerful.

Sebasoni’s testimony as a survivor of the Genocide Against the Tutsi, is part of scores of recorded testimonies held by the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Kigali, Rwanda on genocidearchiverwanda.org.

According to the website where Sebasoni’s story is linked, “the testimony discusses family life before the Genocide, events leading up to the Genocide, intimidation during the Genocide, death of family members, hiding during the Genocide, surviving a mass execution, life after the Genocide, hope for the future and different views on forgiveness, justice and Genocide.”

Sebasoni has dedicated much of her adult life to teaching others about the peace and reconciliation process after genocide.